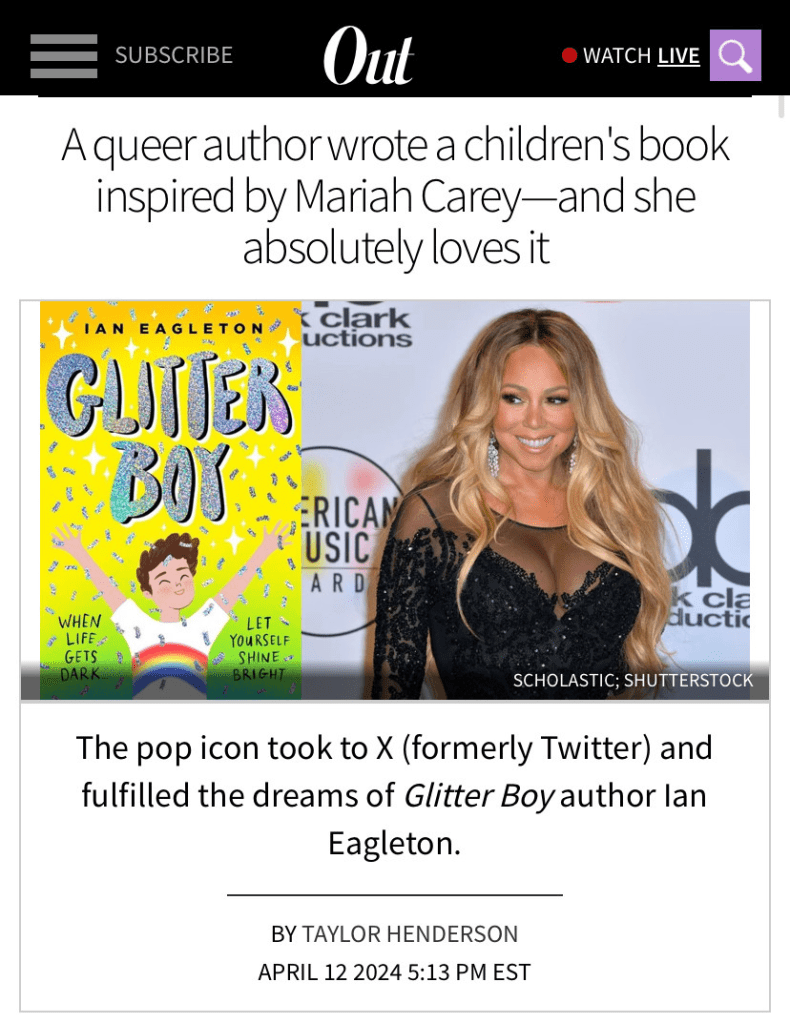

Ian Eagleton, like most children’s authors I’ve spoken to via social media, is actually one of the loveliest people. I remember watching on Twitter, back in the day, when Mariah Carey – yes, ACTUALLY Mariah Carey – praised his book. It was one of – if not the most – magical thing I ever saw unfold on the platform.

Naturally, being a trendsetter, I’d already read Glitter Boy by that point, and I absolutely agreed.

Glitter Boy is a story about grief, and figuring out who you are, and acceptance, and hope. It follows James, who loves dancing to Mariah Carey with his Nan, but who is being bullied at school for being gay, even though that’s not a label he’s attached to himself. While James is very much the main character, the main character arc of the story – to me at least – felt like James’s dad’s. Initially, he spends a good chunk of the book trying to get James to conform, in an effort to make his life easier, but towards the end, he accepts that it’s everyone else who needs to change, and becomes a good advocate for James.

I really love the complex and loving family that Eagleton has written in this book – I love that James’s dad is the primary carer, and that he needs to work through his own ideas of what masculinity means in order to better be there for his son. I love that some questionable actions are coming from a place of good intentions; parents are fallible and in having James’s dad own his mistakes, it almost gives any parents reading permission to do so. And it lets young readers see that change is possible, that grown-ups can be wrong too – and that we can right ourselves. The reasons James’s dad gives for his actions might also help children to understand some of the – admittedly questionable – choices adults make.

I think I said this before, when speaking about Jamie by LD Lapinski, but I’m never really sure how much of myself to put into these reviews. Books are art, and good art elicits emotion, after all. So, I think mentioning my own relationship with my Nan adds something here. My Nan – my best friend – died when I was in my early 20s; I was in the final throes of my dissertation and working an almost-full time job to get by. I didn’t really have time to grieve. My grief came in little waves at inconvenient moments through the later years. Reading this book and getting to grieve along with James was cathartic, even after all this time. So if there has been a death in your family, this might be the ideal book to offer to any child currently grieving.

What are your favourite books with fallible adult characters? Have you read Glitter Boy yet, or did you see Mariah’s post? As ever, I would love to hear from you.

___

I’ve set up a ‘bookshop‘ of sorts, over on Bookshop.org, so that I can point you to somewhere to buy that isn’t Amazon. I get a small commission for any sales made there. This helps to support me running this blog. If you’d like to get your copy of Glitter Boy this way, please just click here. If you’d like to support me without buying a book, you can do so here. Thank you.