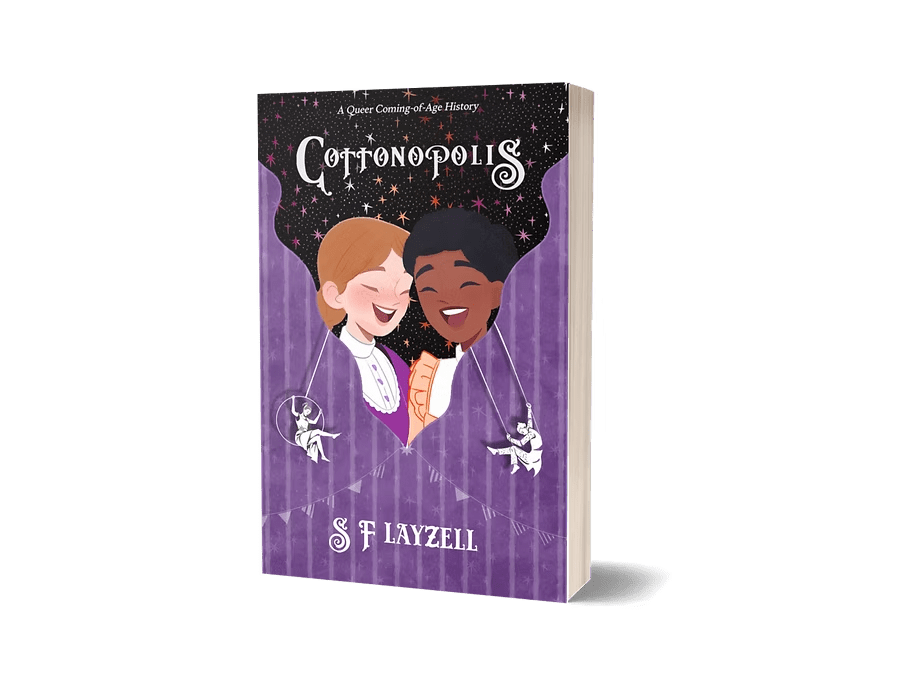

A few weeks back, I took part in a Northodox Pride Party author panel, chaired by the lovely SF Layzell – which was absolutely brilliant for so many reasons. Not only did I get to chat to some other great authors, but I also got to hear about Layzell’s book, Cottonopolis. AND I was lucky enough to get an extract to post here!!

Recently longlisted for the Little Rebels Children’s Book Award 2025, Cottonopolis is a story of family, friendship and first love, with a twist of magic, set in Victorian Manchester. It’s the story of Irish mill girl Nellie Doyle, who works hard to take care of her little brothers, and her growing friendship with Chloe Valentine, who is in search of a better life away from Manchester’s notorious workhouse.

In the extract below, Nellie and Chloe meet for the first time. Both have stepped away from their work, enticed by the sight and smells of a new bakery stacked high with goods neither of them can afford.

I follow the pickpocketing boy through the crowd, hoping to see the bakery for myself. What does the best bread look like? It must be something to bring such a crowd.

A shiver runs through me as the bakery door swings open and a sweet, full smell drifts out. It’s heaven. I can taste it!

I feel like I can almost reach out and grab a handful of it to take home in my pocket. Just imagine the boys’ faces, if I could reach into my pocket and pull out a fistful of this smell, shining like gold, and let my fingers ease apart ever so slightly to let just a little of it out, unfurling and filling their little nostrils.

I’m pressed forward by a sudden rush of people and part of me finds a little pleasure in knowing that some of them will find their purses lighter than they expected when they come to pay. People leaving the shop push in the opposite direction to the rest of the crowd, making me feel like a pebble lost deep in the swirling sludge of the Medlock. As they pass, I get a faint whiff of the sweet smelling delights every one of them carries, wrapped up in tiny individual boxes, each tied with a thin black velvet ribbon.

After what seems like an age (and I’m sure I’m going to be in trouble when I get back, though I can’t seem to pull myself away), I reach the big shop window. The window is a wonder in itself, a smooth clean sheet of glass. A sea of breads and cakes spreads out before me, stretched and cut and moulded into beautiful shapes. There are sticky round buns coated in syrup and dusted with spices, plaits of flaky pastry sprinkled with tiny white nuts and purple flowers made out of sugar, and cut-out golden discs layered with firm custard, fresh red fruits and dollops of yellow cream.

‘Makes you sick, doesn’t it,’ a tight angry voice rings out beside me. I jump back from the window, the spell broken, and find myself staring into the face of a girl about my age. The way she speaks is sharp and quick but full of feeling. English. Like the pickpocket boy. That’s where the similarities end though.

____

Sounds brilliant, right? Here’s the blurb, in case you want any more information….

Welcome to 1840s ManchesterTwelve-year-old mill girl NELLIE DOYLE faces eviction and starvation when her father loses his job. But growing up in the notorious Manchester slum of Little Ireland has made her plucky. She befriends CHLOE VALENTINE and has a chance meeting with a circus owner who seemingly grants seven wishes. They embark on a journey to improve their circumstances. Amidst wishes for peace, freedom, and family reunion, Nellie realizes her growing feelings for Chloe, learning that magic doesn’t always work as expected, and sometimes, you must create your own.

Aaaand, here’s some more details about the Little Rebels awards:

I’m waiting for pay day, and then I’m going to grab myself a copy to review. I just wanted to highlight this book as part of the many amazing LGBTQIA+ books that I’m showcasing this June.

___

I’ve set up a ‘bookshop‘ of sorts, over on Bookshop.org, so that I can point you to somewhere to buy that isn’t Amazon. I get a small commission for any sales made there. This helps to support me running this blog.

If you’d like to get your copy of Cottonopolis, please just click here to support the publisher, or to buy from the bookshop Queer Lit. If you’d like to support me without buying a book, you can do so here. Thank you.

DISCLOSURE: My own book – When The Giants Passed Through – will also be published by Northodox Press.